Last Week’s IPCC Report is Code Red for Humanity. Is it also the end of Net-Zero by 2050?

By James Vaccaro, August 2021

Last week’s IPCC report updates our understanding and our outlook on climate change. Given that the findings in the report are not really a surprise for those working in this field, the real question is how it should impact our strategy. Crucially, are the targets we are now pursuing – principally, ‘Net Zero by 2050’ – still up to the task in helping us manage the impending crisis?

Zero is a nice round number. It’s a well-understood figure that translates easily across languages and cultures. Getting to zero climate emissions defines a fixed endpoint which is why ‘Net Zero by 2050’ was a catchier way of saying ‘aligning to the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement’ (Which goals? 2 degrees or 1.5 degrees? By when? Measuring what?).

How we communicate a goal can either be galvanising or confusing for people seeking to align their behaviours; that is something we’ve seen a lot over the past 18 months as governments have responded to the Covid-19 pandemic.

When ‘Net Zero by 2050’ was first proposed as a proxy target for maintaining a safe climate, it sought to translate a scientific model into a global economy model. However, the science was based upon averages across the entire globe – there were no specifics for individual companies or countries. The scientific model was not predicated on precarious or remote carbon removal technologies (although it allows for their possibility). It was not rooted in offset markets which might delay primary carbon reductions. And it was not based upon most of the reductions in emissions coming toward the end of the period up to 2050 (a convex transition, leading to the ‘area under the curve’ – and therefore cumulative emissions – being considerably greater than either a linear or a concave transition).

But leaving the bulk of reforms for later is the behavioural reality for ‘Net Zero by 2050’, and the IPCC report makes it abundantly clear that we must revisit it as a target. It may have served a purpose in activating some stakeholders, but has become victim to Goodhart’s Law: ‘when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure’. That adage flows from the observation that once you pin down a target it’s wrong to assume that everything else will stay the same; instead, relevant conditions may well flex to produce unintended consequences.

But let’s not throw away the zero ‘baby’ with the net-zero 2050 bathwater. If we retain the framework but ground it in the latest IPCC data and the realities of behavioural economics, we’re likely to require Net Zero targets to be met by companies and countries considerably earlier – probably somewhere between 2030 and 2035 (respectively the targets of Uruguay and Finland).

Shifting the Timeline

Shifting to a 10- to 15-year time horizon would have several beneficial consequences for how financial flows are allocated right now. For example, (1) being 10 years rather than 30 years away from our target date makes the target far more likely to impact financial investment time horizons. (2) It increases the likelihood that finance and industry would stop adding to the problem and we’d start to see a ‘concave’ transition. (3) It reduces the reliance on offset strategies or technologies which are still theoretical. (4) It could also reduce transitional chaos, with more chance of social safety nets for society. By contrast, our current situation of backloading the bulk of reforms leaves citizens facing potentially catastrophic disruption with little or no contingency planning.

In considering our response to global climate catastrophe, we can look to the example of Covid-19. Recovery funds from the pandemic have been significant in volume, but hugely disappointing in sustainability terms despite the ‘build back better’ narrative (macroeconomics, as it turns out, needs more than a ‘what three words’ exercise). But Covid-19 recovery funds are predicated on government borrowing which in turn is predicated on future economic recovery and expansion. Critically, what enables credit is belief that the future will provide the means to pay back. But climate change is not a blip which will get better – it is a tidal wave which could take centuries to reverse. So government credit will be more difficult, meaning the prospects of social safety nets for those without the means to protect themselves will become vanishingly small. And there are no simple spend-your-way-out strategies or vaccines for mass droughts, floods, fires and storms.

COP26 President Alok Sharma said last week that ‘we’re on the brink of catastrophe’ and that ‘this is our last hope for 1.5oC’. Yet he then went on to say that his own UK government would continue to permit further North Sea oil exploration and development, despite the IEA warning in May this year that new expansion and exploration of fossil fuels was not compatible with 1.5-degrees. The UK government hosting COP26 wants its ‘cake and to eat it, too’ (the gain without the pain) or as they put it in their North Sea Transition Deal, ‘to support the sector in a transition to lower-carbon energy sources, while extracting value from the remaining potential on the UK Continental Shelf.’ If everyone was to do the same then we would be beyond the ‘brink of catastrophe’ being referred to, so the actions being contemplated fail to match the words.

Looking to the 2030’s

You cannot manage what you do not measure. But maybe there’s a subset of conditions that we cannot manage whether we measure them or not – like the reversal of climate change once we lose control of the situation. The IPCC report makes clear that this point happens when we reach 1.5oC and that point is approaching by the end of the decade. The fact that older Arctic sea ice is being blown into the melt zone, is a sign that feedback loops are being initiated which we will not have the capabilities to reverse. Across the world, forests now being ravaged by fire could theoretically be replanted, but it will take decades to restore the carbon storage lost from these events (saplings sequester very little carbon) and there’s increasing risk of future forest loss as climate changes.

So if we really want to update our global climate target, recognising there will be laggards, setbacks and contingencies to plan for, we should focus our reforms on what is technically feasible now (somewhere in the early 2030s), not in what is commercially feasible (probably somewhere in the mid 2050s).

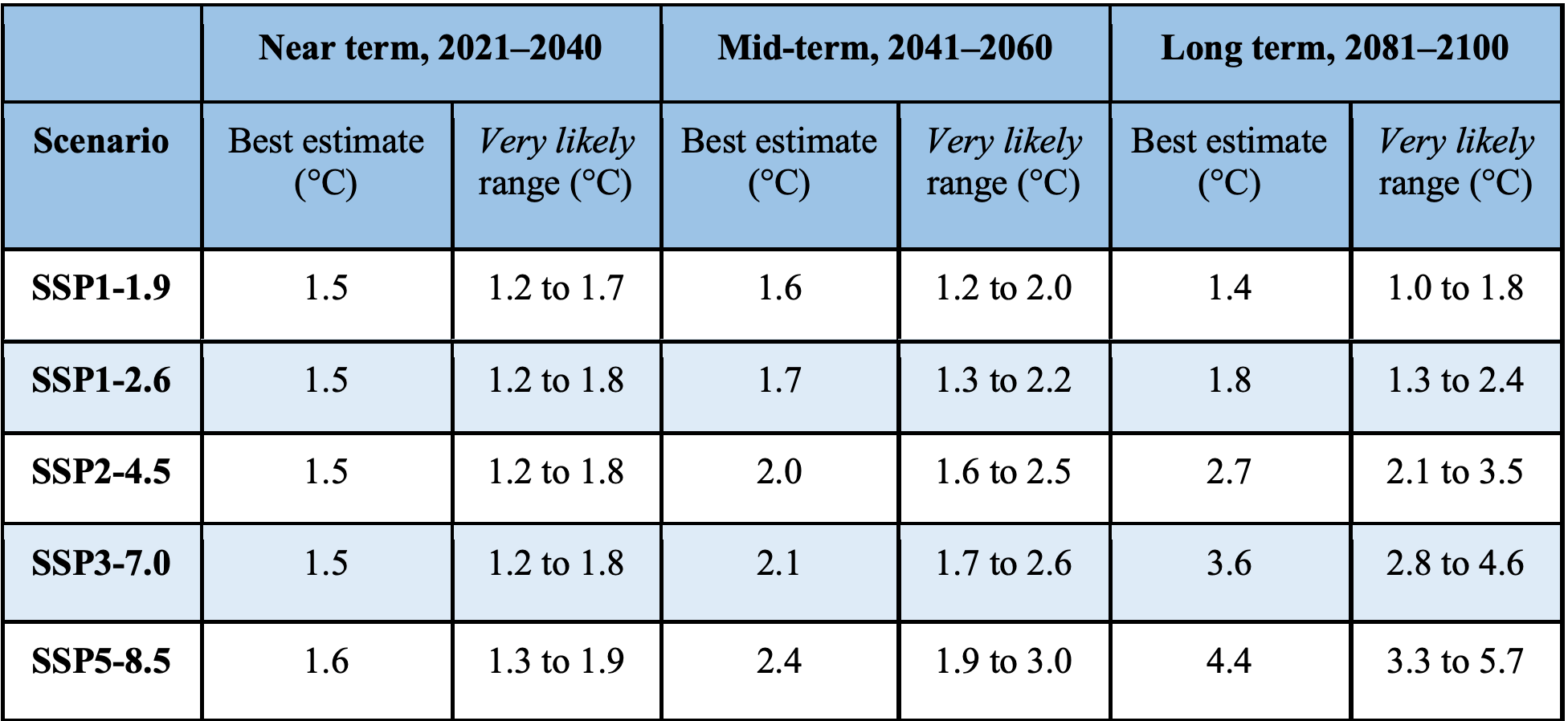

Again, we can look to the example of Covid. Its global economic damage is likely to total $28trillion – a hammer blow to the global economy over the space of a couple of years – but one from which we might (possibly) bounce back. The damage from climate change will be far greater. It will also be ‘locked-in’ over the remainder of the century with cumulative impacts emerging long after the climate emissions enter the atmosphere. The IPCC’s data project little variation in what happens to temperatures up to 2040 between rapid transition and business-as-usual scenarios. But they diverge very significantly by 2060 (which I think of as the year my eight-year-old daughter will be my current age) and are unrecognisably different by the end of the century (a good 50 years longer than the horizon of central bank stress tests).

We may have squandered the possibility of ‘gradual transition’ but there is still hope to maintain a 1.5oC limit. Coal may become history – albeit decades late. Natural gas may have been a transition fuel; it isn’t any longer and needs to be run-off and replaced with renewables. The IPCC used to just be of interest to climate scientists; it’s now noticed by all as we become increasingly aware we are burning our future. And ‘Net Zero by 2050’, until recently a useful measure, is not that any longer. COP26 needs to find a new target if we are to achieve climate safety in the future.

*****